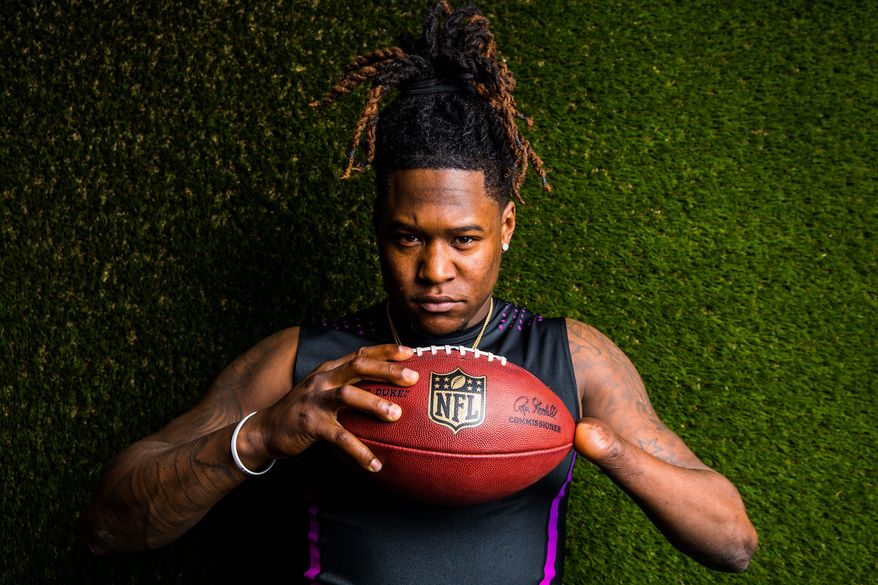

Griffin’s goal to reach NFL one-handed is more than a notion

By DERON SNYDER (as published in The Washington Times)

Can you conceive being without your left hand since childhood? Can you envision the various reactions from classmates, some mean-spirited and perhaps some kind, but all of them curious?

Can you imagine the stares and questions? The taunts and putdowns? The sympathy and pity that was unnecessary, unhelpful and unwanted?

Shaquem Griffin doesn’t have to imagine it. He’s living it.

The linebacker from Central Florida was a late invitee to the NFL Scouting Combine but he left a lasting impression, in the weight room, on the track and at the microphone. Born with a rare birth condition that led to an amputation at age four, Griffin put the focus on what he brings, not what he’s missing.

Sure, he proved himself at UCF where he twice was an all-American Athletic Conference first-team selection, winning the 2016 Defensive Player of the Year award. A captain on last season’s undefeated team, Griffin made plays all over the field and capped his college career with 12 tackles and 1.5 sacks in a Peach Bowl victory against Auburn.

But the NFL was unconvinced. Griffin wasn’t invited to the Combine until after an impressive week at the Senior Bowl, where the hybrid defender saw work on the line, at linebacker and in the secondary.

He blew away observers Saturday, completing 20 reps in the 225-pound bench press (a higher total than 10 offensive linemen). On Sunday, his time of 4.38 seconds in the 40-yard dash was the fastest by a linebacker at the Combine since 2003.

“So many people are going to have doubts about what I can do,” Griffin told reporters. “There’s going to be a lot more doubters saying what I can’t do, and I’m ready to prove them wrong.”

Looking for prospects’ weaknesses is half the job for NFL scouts and executives. Turning in one-sided lists – all strengths – will get you kicked out of the club. Measurables like height, speed and weight are low-hanging fruit, easy to mention when they don’t match the ideals.

Being one-handed casts Griffin’s other numbers in a different light.

But questions about their pro potential is part of the process for every player, including those with two hands.

Take, for instance, Louisville quarterback Lamar Jackson, who knocked down suggestions at the Combine that he might switch positions. The notion was raised last month when ESPN analyst Bill Polian said the Heisman Trophy winner should play wide receiver in the NFL due to his accuracy, height and frame.

Never mind that potential No. 1 pick Josh Allen was less accurate against lesser competition, and several established NFL QBs are similar, shorter or slighter compared to Jackson. (I’m strictly a quarterback,” he told reporters Friday. “Whoever likes me at quarterback, that’s where I’m going. That’s strictly my position.)

You can decide for yourself, but I suspect the league’s long, shameful history regarding black quarterbacks is a factor in Jackson’s case.

In Griffin’s case, there is no history for skepticism, because there has never been a one-handed player in the NFL’s modern era.

Jim Abbott might be the patron saint for athletes like Griffin who aspire to be pros. Born without a right hand, Abbott pitched for four major-league teams over 10 seasons, winning 18 games for the Angels in 1991 and finishing third in American League Cy Young voting. In 1993, he threw a no-hitter for the Yankees.

Abbott inspired everyone who saw him pitch. Griffin has the same effect as he terrorizes quarterbacks and ball carriers. But his mission extends beyond playing in the NFL and being a role model for others who are underestimated and undervalued.

“I know that there are a lot of kids out there with various deformities or birth defects or whatever labels people want to put on them, and they’re going to be doubted, too,” he wrote on The Players’ Tribune in an open letter to NFL GMs.

“And I’m convinced that God has put me on this earth for a reason, and that reason is to show people that it doesn’t matter what anybody else says, because people are going to doubt you regardless. That’s a fact of life for everybody, but especially for those with birth defects or other so-called disabilities.”

Griffin still might not cut it as NFL player. He can live with that.

If so, he doesn’t want anyone to blame it on his missing left hand. He’s either good enough or not, period.

But so far – from being an 8-year-old who slept in his jersey the night before games, to being a 22-year-old who captivated at the Combine – so good.

— Brooklyn-born and Howard-educated, Deron Snyder writes his award-winning column for The Washington Times on Tuesdays and Thursdays. Follow him on Twitter @DeronSnyder.

Follow

Follow